KOKA SHASTRA

By Santosh Ghosh

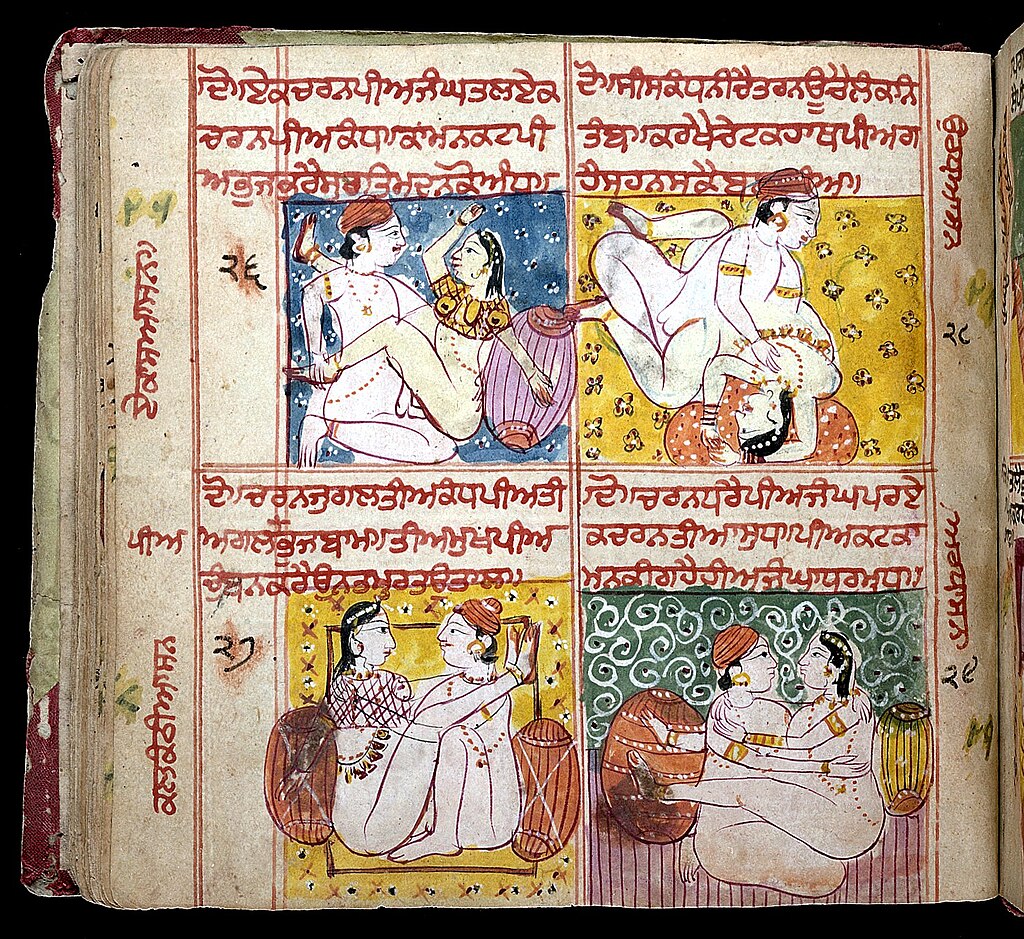

Koka Shastra of famous Indian erotic work on love. Kama Sutra was a great success in its own time, eclipsing all previous work, and it has been recognised as a masterpiece in India ever since. In the sixteen centuries since its composition no imitator, and there have been many, has even remotely challenged it’s pre-eminence. The most famous of the mediaeval text are the Koka Shastra of Koka Pandit ( Koka’s Treatise) follow Kama Sutra for much of its length, although adding a new classification of women and many sexual postures not found in Vatsyayana.

Koka Shastra most popular work and this you may buy on almost any street corner in the city of India today. Shrink-wrapped in the garish yellow cellophane, they are known as ‘yellow books’ and rejoice in titles like Koka Shastra (असली कोक शास्त्र) or Old Kama Sutra. That they have nothing whatsoever in common with the texts they claim to represent is illuminated by the extraordinary statement in Old Kama Sutra that : ‘A man should intercourse when his nose blows.’ ( Sinha : 1933 ).

Genisis or Origin of Koka Shastra ( Ratirahasya) : Is widely accepted as the post rare story on erotics, written by Koka Pandit during the reign of the celebrated Hindu Raja Bhojadeva was a great legendary figure in Malwa ( Central India). We set apart from a mythical character of Koka Pandit was mantri ( Minister) to the Highness the Maharaja Bhoj-Puram of Malwa, here, we told related an incident from the colourful and voluptuous life of the mediaeval Eroticism Koka Pandit, cited as being the most virile man in all of India’s history, was said to have carnally known thousands of women and succubi.

As an author of Koka Shastra, the secret of Conjugal bliss, has been severely named. Koka began as a regional Eroticist and we have point out his contribution to the science of erotics originates from several aspects and these appear for first time in Koka Shastra, and indeed which are conspicuous by their absence in Kamasutra.

This Learned Story on erotics, Koka Shastra ( Rati Rahasya ) was written by Pandit Koka, during the reign of the celebrated Hindu Raja Bhojadeva was a great legendary figure in Central India. He belonged to the Paramara dynasty and ruled over forty years on the throne of Dhara of Malwa.

In Indian history, the era of the scholar Raja Bhojadeva, has been aptly regarded as a most brilliant period in the history of Sanskrit literature. As rules, Raja Bhojadeva was also most powerful principality. Koka Pandita was mantri ( Minister) to the History Highness the Maharaja Bhoj-puram of Malwa.

The Koka Shastra is generally known in India as Rati Rahasya after the illustrious author about whom the following tale is told :

A woman who was burning with love and could find none to satisfy her inordinate desire, threw off her clothes and swore she would wander the world naked till she met with her match. In this condition she entered the levee-hall of the Raja Bhojadeva upon whom Pandit Koka was attending ; and, when asked if she were not ashamed of herself, looked insolently at the crowd of courtiers arround her and scornfully declared that there was not a man in the room. The king and his company we’re sorry abashed ; but the Pandit joining his hands, applied with due humility for royal permission to tame the shrew.

He then led her home and worked so persuasively that well-nigh fainting from fatigue and from repeated orgasms she cried for quarter. There upon the virile professor inserted gold pins into her arms and legs and leading her before his prince, made her confess her defeat and solemnly veil herself in the presence.

The Raja was, as might be expected, anxious to learn how the victory had been won, and commanded Koka to tell his tale. The Pandit composed his work to please Venu Datta, who was probably a Raja. When writing his own name at the end of each chapter of his book he calls himself ‘Siddha Patiya Pandita’ i.e. an ingenious man among learned man. Under the title of ‘Lizzat-al-Nisa’. The pleasure of enjoying of women, the Koka Shastra has been translated into many language of East, including Arabic and Persian, Turkish and Hindustani ( Roy : 1950 ).

Another related an incident from the colourful and voluptuous life of the mediaeval Eroticist Koka Pandit, minister -of-state to the eleventh century court of the Maharaja Bhoja. Koka Pandit, cited as being the most virile man in all of India’s history, was said to have carnally known thousands of women and succubi.

The eminent Panditji, ever searching for the female or spirit capable of serviving his furious assault, one day heard tell of a secret and forbidden cave in the forests of Malwa.

There abides in the cave a young priestess’, a wizenced old garu told him. ‘She is what we holy men called ‘jigger-khawish’, a liver-eater. She is capable of snatching away the liver of a man by mere glance and incantations. Glaring into the eyes, she has mesmerized the most unwilling of men. She then obtains their seed, tosses it on to the flames of sacrifice, when upon the man dies. This has been seen, and not even I can deny it. The ashes of her victims are strewn round her abode. She, as pythoness, possesses an infinite knowledge of all that occurs ; for she discerns the future of mankind. You must be wary of ‘nangidevi’, O my Panditji. Nangidevi has been likened to the ‘pesachi’, she-demon of the gods’.

Koka smiled, raising his hand. ‘No she-demon has ever worn me down, O must sublime Guruji. ‘yukshi’ and ‘bootni’ : all of them have wept with fatigue. His Highness can attest to that’.

‘Ah! but she is ever more powerful than the succubi, who come in the night to torment man till there can be no distinction between reality and illusion’.

But Koka only laughed, filled the Guru’s begging cup, and demanded to know the course he must take. The old holy man shrugged, shook his head, and reluctantly showed him the way.

In the hazi of evening, Koka Pandit want cautiously through heavy thicket that led into a ‘nullah’ a sort of gulley, from which Rose a fetid stream. The odour of decay was thick and gagging in Koka’s nostrils.

Then the cave yawned before him. It was, at first glance, majestically embellished. An archway of polished ‘choonum’ ( shell-lime ) glowed primrose in wraith like dimness, and Koka could see that each pillar was adorned with the most intricately carved figures. He drew closer, momentarily caught up in the enchantment.

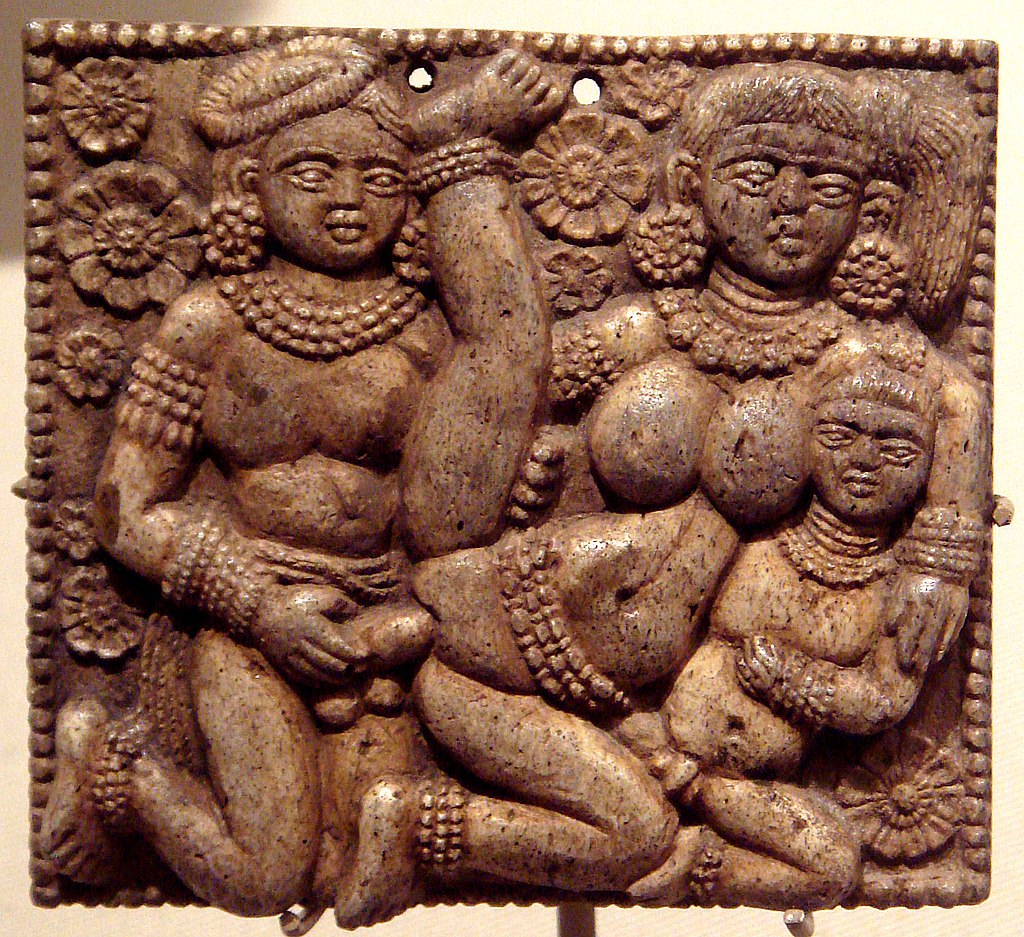

Koka had studied many of his native temples, but rarely had he behold in any such a display of the indulgences and delights of Paradise. Shiva was smiling as Parvati enswathed his waist in the act of coition. Beside them he saw the naked ‘rakasi’ and ‘pisaci’ guardians of Lord Shiva and his lustful spouse, in every conceivable position. Some, being ‘rakasi’ we’re standing with ‘pisaci’ entwined about their waists, their lips joined in bliss.

Others, in perfect symmetry, we’re touching or founding one another’s secret parts. Koka saw man and beast locked in ecstasy ; willowy goddesses with swelling breasts embracing ‘Hanuman’ the Monkey-God ; another image of Mahadeva, the Queen of Serpents, coiled about him, devouring his swollen ‘lingam’. Then, to finish the panorama and from a cornerstone, there stood in bas-relief a row of naked Virgins with spherical bosoms and vulvae delineated in precise details.

Koka groped towards the light, an orb of white heart, in a vacuous den of darkness. As further on he sought, carefully placing his feet so that he would not blunder into a pit, Koka noticed that the light seemed to Dim as if it were escaping his grasp.

The vault was hot, ominously still as before thunder. He stopped, nervously unfastened his robe. Sweat rushed from his scalp ; it soaked his face, and neck, and chest. He felt it uncomfortably upon his limbs. Koka wiped his face, and wrapped the shirt of his ‘pugree’ about his neck. He edged forward.

A vibrating brilliance struck his eyes. Koka lurched back, shielding his face. Heat overwhelmed him, crushing. Flaming images hugged his body, so that he dropped to the ground. Koka thrashed to grip his senses, and there was daylight. A seductive infinity of luscious verdure, glimmering ponds, billowy groves, swelled before his eyes. Then, there was utter darkness. A voice, as from a conch-shell : ‘Ashirvadam, ey Maharajjee’ ! ( Blessings and welcome, O Great Lord ).

Koka grappled to gain his feet. He stumbled, clawing, clawing the thickness of atmosphere round him.

A vague luminescence pulsed before him, intensifying with the beat of his heart, until it flared rich and yellow. A hand, apart from its arm, quivered in keen silhouette. The middle finger was raised, and thumb and forefinger were squeezed rightly together in the classic sign of ‘lingam- yoni’.

Koka pressed his eyes shut, gasping with disbelief ; but the hand remained for what seems many years. Then, the hand dissolved. Brilliance blazed over the vast, drumming caverns and Koka saw blood, reeking, spelling over a sea of beauty. He was blinded by its sinister glare.

Koka heard the faint strains of the ‘lute’ like sitar. The green mists swirled, fumed saffron, then dissolved into the naked glare of sunlight. Koka emitted a long, Sharp cry, starting back on his haunches. He looked upon a ‘bazaar’ and a face in the bazaar. It was his own face, a laughing face. The face called out to women who sat of their Windows above the street, warbling lewd ballads and pouting with ‘henna’- stained lips, beckoning with bangled wrists and lithe fingers. Koka watched himself walking on and on into dimness, into night. And every movement, every sensation, prodded his his rigid body. A million voices in his ears, a millions brushing past ; his own words and gestures, acknowledged as though he were there and performing as a puppet must perform.

He laughed, and the lough echoed, wild and sepulchral. And as Koka Pandit looked into his own eyes, he saw the deep brown waxing into green, blazing viperous emeralds, which shrilled an evil tint of lust.

The voices dimmed, the images fled ; the night fell in eerie rose tints. He entered a strange apartment. Every nerve reacted, every sense gripped what lay before him. A shimmering willow branch rushing towards him seized his body in a hungry embrace. He could feel his every tissue responding to fierce stimuli as his hands clutched soft flesh, as he grasped the foamy shroud, rending it down, to reach firm, pointed breasts, marble-white and demanding.

Koka shuddered, his mouth gaping. The sleek arms were taut about his neck ; sinuses limbs were as creepers, enwreathing his body. A flash of demoniac buoyance took hold of him and the Savage ecstasy began to build, pleasurable incisive, as her image moved against him. And her lips sought his own, her tongue his own ; and she scarred his back with her nails, and she cried out in rapture, then groaned in a convulsive instant of release.

Koka felt inebriant pleasure as he sank into unconsciousness. His body was yet her body ; and she clung to him fervently, humming in delirium. But just as he became aware to slowly edging into darkness, a bolt of fire seared his brain. Koka pitched forward, glared at her ; and blood, sickeningly bright, was upon her arms and body, and blood bubbled from his breasts. Her hand was upon the dagger, and the dagger was in his heart. But he felt no pain, only loathing. He screamed, clutched her throat and dug with thumbs of pliant steel until she was dead.

He swayed, his eyes sightless. His fingers trembled, touched a floor of nothingness. Koka seemed to disintegrate ; he eased back, plunging into a howling void.

Several hours later, Koka Pandit groped for his senses, found himself naked and alone ! The vague hazy light of early morning allowed him to find his clothing. He seemed weak, taxed in all his muscles, as if he had endured many hours of labour. A shrill blue belaboured his reason, having need to shatter it, so that he could not think or move.

Searching the cave from one end to the other, he discovered nothing. And the entire night remained with him as the memory of no other dream ever had. Reality was lost in illusion, but illusion brought before him the frightful truth :

‘No man is a god,

No man has the power of

Lord Shiva’.

Koka Pandit, unable to cope with the supernatural, resume his search for a woman to equal his strength. Such a one, Koka promised, he would take as his bride, and settle down in the palace to a normal family life. Otherwise, by the immutable wills of fate and Lord Shiva, he dedicated himself to the study and impregnation of all womankind.

Learning of the offer of a famous Rajput Courtesan that she would make any living man fabulously wealthy who carnally satisfied her, Koka went to investigate. Her rumoured boast was that no one had equalled her in physical endurance, and she had yet to encounter man or spirit to match her. Thus, having learned his own lesson, Koka Pandit eagerly ventured forth to instruct another that :

‘No woman is a Goddess,

No woman has the power of

Mother of Parvati’.

‘Ah, so thou art’ just another presumptuous one. I wish to see the coin first ; it shall not be long ere I must take it away from thee. No man has ever been that rare that he can leave as wealthy as when he entered’.

In stifling dimness, Koka naked feet stood velvet ; and he said nothing. She glared at him, grinning. ‘What is thy name ?’

Koka glared back at her, his lips vaguely twisted.

Then she came forward and stroked his cheek. Unbuttoning his damask robe, she pulled it open and smoothed her hand over his chest. ‘Thou art a strong man’, she said, expressionless. She never once took her eyes off him, nor did Koka cease to gaze at her.

She then embraced him, tightly. He fought desire ; he did not want to Fall prey. Koka could feel her unfastening the string of his trousers. Then, as if by instinct, her work hand sought and gripped with an uncanny deftness. It sent chills rushing through his body.

‘You tremble’.

He glared at her, his lips unmoving.

Thou art surely an ‘avater’, she sighed, forcing her lissome body against him. She bit his neck, to hear his voice. Koka clenched his teeth, did not utter a sound. Her hands and bare thighs we’re at their work so that it was agony to suppress himself. She again looked into his eyes, and smiled viciously. ‘ Thou wilt not seem vain and cocksure like all the others. Thou wilt drive me to exertion ; and then , ‘ey Hurree ! Surely, years must slay me’.

Koka grasped her, and she shrilled acceptance. Her arms were tight about his neck ; and she cooed, then hissed, heer fingernails sharp upon his back.

‘When the sky becometh dark’, she whispered heartedly, through the excess of our love, fires are kindled within our bosoms, flaring white-hot in our loins, and sleep is driven from our bed, and often our bodies afflicted by rabid desire’.

Koka, able and sure, was coarse but ardent with her, like iger with tigress, and it was what she demanded. Rending her sari garments, he pressed her to the cushions and marked her shoulder with his teeth. And his fingers streaked, so that she gasped and trembled and dug her nails into his flash. Then, he whispered to her :

‘I am Koka Pandit, ‘mantri’ to His Highness the Maharaja Bhoj-puram of Malwa’.

She screamed, spat in his face. Thou dog ! though thou wert His Highness in a person, thou hast offended me’. She sought to gouge out his eyes, but Koka grabbed her wrists and held them so that she gasped for mercy. The ‘Rajputani’ glowered at him, sneering : ‘Why hast thou come to taunt me ? ‘Ey Hurree ! I would walk through fire if I could but bear one of the children, to know that I was penetrated by a stallion, that the seed of bulls was in my womb, and that I bred a king in glorious honour of Lord Vishnu. But you laugh at me, you take me by deception. Yet, in truth, no man or spirit has ever cudgelled me into subjection’.

Koka Laughed. ‘Show me your skill’.

‘I will show your death !’ Her hand darted under a pillow. Koka saw the deadly flare of steel, lurched aside, then fastened both hands upon her arms. She moaned, and the blade fell fully to the floor. Koka seized the dagger, lossed it across the room.

‘Princess !’ he said.

Her cheeks reddened slightly. Then, as though her eyes and manner were governed by sorcery, she regarded him, intense, magnetic. She pitched forward, clutching him by the shoulders. ‘I am a lioness ; I am a leopard’s mate. I am thinking for one million years’.

He glared hard and earnestly at her, taking her arms firmly but gently. She uttered a weak cry ; and he caught her parting mouth to his own, drawing her tenderly upon her on the silken cushions. She clung to him in a sudden fever of awe and spasmodic need. His hands tightened on her thighs.

‘Ey Hurree ! Hurree ! appease me’, she sighed.

Koka lurched to his feet. Down was bursting over the copper green topes ( mango groves). Only a few moments before, the eminent and inexhaustible Rajputani had fainted under him. Searching his ‘pagri,’ Koka laid two hundred rupees next to her body and, slightly dizzy, staggered out the gagging chamber.

To be sure, his vigorous trial with the spiritual world had rendered him more than capable of defeating the most redoubtable Courtesan in all of India ( Allen: 1959).

KOKA PANDIT AUTHOR

The author of Koka Shastra, the ‘Secret of Conjugal Bliss’, has been severely named as Kokkaka, Kokkoka, Kokah, Koka, Kukkoka, Kokadeva, Koka Pandit, and so on. One of them is referred to as Kadvaya by Raghavabhatta in his commentary in Abhignana Shakuntala.

However, we know very little about the author’s personal life, beyond the fact that his grandfather was named Tejoka ; his father, who enjoyed great fame, went by the name of Gadya Vidyadhara Kavi ( Vaidya Vidyota Pandita ), and that Koka himself was honoured among scholars and poets.

In several legends have been woven around the name of Koka. According to one such legend, he was a Kashmiri Brahmin, well versed not only in the science of Erotics but in other occult science as well. However, there is definite evidence to show that he wrote the Koka Shastra or the Rati Rahasya ( Kamakelirahasya ) to please his protege Vainya ( Vaishya ) Datta. Koka wrote the Koka Shastra to satisfy the curiosity of King Vainyadutta. We know from history that one Vainyadutta flourished in about A.D 507 in Bengal. His portrait on his Gold coins is quiet well known to numismatist. We have however no proof to show that protege of Koka and the Gupta king are one and same person.

The author’s main objective appears to be to instruct men in the art of winning over frigid women, or those suffering from sexual anaesthesia. He particularly stresses the methods by which a man may not only gain the attention of women, but in due course, may come to sustain their affection. This is, in fact, what is advocated by the science of Erotics to every man who studies and practice it.

To achieve this ambitious objective, Koka made a thorough study of the works of his predecessors, both in the field of Erotics as well as in other ancillary topics. He contents therefore that Koka Shastra is the quintessence of the wisdom of the sages who wrote about the Ars Amoris.

As regards the date of Koka Shastra, it is now possible to conjecture the period within which it was written, with the help of two vastly differing composition : One, the Haramekhala or Mahuka, composed in v.s 887, i.e, A.D.831 and Second, the Nitivakyamrita of Somadeva Suri.

As we mentioned earlier, Koka drew heavily upon Haramekhala. The other author, Somadeva Suri, refers in his Nitivakyamrita to Koka and his practices as Divakama. As a cross-reference, Koka refers to certain auspicious tithis and yamas, favoured by the Padmini and other types of women for congress, and this epithet Divakama is based on the statements of Koka. Although the date Nitivakyamrita has not yet been accurately ascertained, as we know that Somadeva Suri wrote another work entitled ‘Yashastilaka Champu’ which was definitely completed in Shaka 881, i.e., v.s. 1016, i.e., A.D.959. We may conclude, therefore, that Somadeva and Koka were near contemporaries and that Koka lived sometimes between A.D 830 and 960.

Since the 9th century A.D. Koka had become very widely read, and small wonder then that succeeding authors and commentators, who put Koka Shastra almost on par with the Kama Sutra, used it extensively to explain certain terms in their own works. Here a few examples :

- Harihara ( A.D.1216) On Malati Madhava.

- Narayana Dikshit ( After A.D. 1250) On Vasavadatta.

- Yashodhara ( A.D. 1225-1275 ) On Kamasutra.

- Vemabhupala ( 4th century ) On Amaru Shataka.

- Gangadhara ( A.D.1300-1400) On Malati Madhava.

- Mallinatha ( A.D1430 ) On Megha, Raghu, Kirata, Naishadha, etc.

- Kumbha (A.D. 1433-1469 ) On Gita Govinda

Koka will be remembered by Indians for presenting a most appealing and attractive subject in a very lucid and readable form. It is not generally disputed that Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra, thought a learned collection of Sutras, is not easily understood by a layman without the help of a commentary and Koka’s work undoubtedly serves as a more popular and a more readable version.

Apart from this, Koka’s really invaluable contribution to the science of Erotics originates from several aspects and these appear for the first time in Koka Shastra, and indeed which are conspicuous by their absence in the Kamasutra. Some ideas which he has put forth have been drawn from the works of Nandikeshvara, Gonikaputra, Gonardiya, Muladeva and the work known as Gunapataka all of which are unpublished and comparatively little known. Here, we only know of them through Koka’s some references to and quotation from these work.

Among the original topics which are discussed for the first time by Koka are the following once :

He classified women into four major categories, ‘Padmini, Chitrini, Shankhini and Hastini and tabulated their physical, psychological and sexual characteristics, along with the days and nights and Yamas thereof and postures favourable for each of them for the attainment of the highest Conjugal hapiness. Some writers ( Shringaramanjuri, Ed. Dr. Raghavan), contend that this classification has been lifted from Vatsyayana ; in actual fact, it is conspicuously absent in the Kamasutra.

He has isolated erogenous zones, and further specified certain days of the waxing and the warning Moon ( Chandrakala) as suitable for the verious technique of winning over women.

Although basically he has followed Vatsyayana in classifying women and men into Harini, Vadava, Hastini and Shasha, Vrisha and Ashva, according to the parinaha ( circumference ) and the ayama ( length, depth ) of their respective organs, he gone a step further and detailed their physical, psychological and sexual peculiarities, and the different means to be employed to please them. Koka himself acknowledge

Vatsyayana as his source, but the details are glaringly absent from the Kamasutra.

In the chapters on Vashikaran, he has enumerated mantras or charms named Kameshvara, Kundalini, Hrilekha, Saptakshara and Krishnakshi. He has also given the recipes for Mahsvashikarana oil, Chintamani incense and other preparation for painless child-birth, for the prevention of abortion, for improvement one’s voice, for avoiding body and mouth odours, for uplifting sagging breasts, and also incorporated some of Nagarjuna’s recipes. This in itself is no means contribution, since these recipes are not to be found in the extant text of the Kamasutra.

The author of the works Koka, generally acknowledges the heavy debt he owns to his learned predecessors who wrote on the Science of Erotics, sometimes by actual reference to their names and often to their works. He claimed to place before his readers to quintessence of all the writing on the subject that had preceded him.

The author has used the generic term muni or sage in referring to some of his predecessors, and to identified them, we have to rely on the commentator Kanchinath. There are nine such references, of which four are not identified even by Kanchinath and the fifth is rather uncertainly mentioned.

The authors and their work referred to by Koka, with their respective identities, are as follows : Nandikeshvara, Gonikaputra, Munindra, Munibhih, Karnisuta, Muladeva, Gunapataka, Vatsyayana muni of Kamasutra, Nagarjuna, Shabdarnava, Haramekhala, Udisha, Yagavali and Munayah.

Now we shall try to discover some facts about these authors and the works on Erotics reference to by Koka.

Muladeva and the work entitled Gunapataka : Muladeva had many other pseudonyms with all of which his many disciples were quiet familiar. He also had many patrons who appreciated his proficiency in the verious arts. Mention may be made of a few of his pen-nemes : Mulabhadra, Karnisuta, Bhadra, and Devaduta etc.

These, in fact, have been mentioned in such well-known lexicons as Vaijayanti (A.D.1050) and Haravali ( before A.D.1159), both of which cite his name alongside his pen-nemes as the author of The Art of Thieving. Connotationally, the name Karnisuta implies that Karni was Muladeva’s mother, but we know nothing about his father.

However, about his own attainment we do know a good deal. He was adept in the art of enticing woman and the very personification of chicanery. Crooks, chests, miscreants and all kinds of rogues flocked to him for advance and guidance in their nefarious activities. His two special friends were Vipula and Achala, and his adviser was named Shasha or Shashi. He held court at night, usually brilliant with moonlight, attended by his followers, chief of whom was one named Kandali, and his friends like Shashi. While addressing these followers and admirers, he spoke from a resplendent dais.

As a result of his specialised learning, a large fortune accrued to him, and, in fact, it become essential for every young man’s education to learn something of these arts from Muladeva. Many found parents left their sons in his care and Kshemendra gives in an instance of a certain wealthy merchant, Hiranyagupta, who entrusted his son Chandragupta’s education to Muladeva’s care.

Muladeva’s fame spread far and wide in the course of time, and his name come to be automatically linked with the amorous art. It precisely for this reason that Vatsyayana actually used the derivative term ‘Mulakarma’ to describe the art of enticing women. Yashodhara in his commentary ‘Jayamangala’ on these Sutras perhaps coud not grasp the meaning of Mula and that is why he has not expected the association of the name of Mula ( deva ) with these acts.

Amar Sinha, the famous lexicographer, also saw the connection, and used Mulakarma as the synonym of Vashakriya ( the art of enticing ) and Karunmana ( Magic, watchcraft ). Also, Muladeva has been immortalised in Sanskrit classical literature through these verious references :

Subandhu while describing the Svayamvara of Vasavadatta refers to him as Kalankura. Dandin refers to the acts and the way of life of Karnisuta. Bana, in his Kadambari, while describing the Vindhya forest, refers to Karnisuta and his friends Vipula and Achala and his adviser Shasha. Bhanu Chandra, the commentator, further informs us that he was the propounder of the Science of Thieving and his group consisted of Vipula and Achala and Shashi acted as an advisor.

Mahuka, the author of Haramekhala, refers to Muladeva and the divine gift of yogic power granted him. Koka refers to Muladeva when he describes the sexual characteristics of the women of Utkala province. Kshemendra in many of his works mentions Muladeva and his nocturnal gathering.

Somadeva in his Kathasaritsagara makes Muladeva the subject of a story, and goes so far as to describe him as the Prince of Rogues, whose chief adviser was Shashi.

Again, Yashodhara, who wrote his commentary Jayamangala on the Kamasutra, refers to Muladeva while describing Sangharsha or the completion that took place between two Courtesans name Devadatta and Anangasena for the love of Muladeva.

Now let us consider if Muladeva wrote anything incorporating his teaching for benifit of his own pupils and others interested in these topics. To begin with, it can be concluded that from the very nature of his activities he was well-known personally among Courtesans. Indeed, we have on record a statement by Yashodhara that two Courtesans vied with each other for the affection of Muladeva. We can conjecture that he became deeply attached to one such Courtesans named Gunapataka whom he instructed and who eventually emerged as an adept at his own Art. Muladeva titled on of his works after this Courtesan, and it is possible that he did so to perpetuate his own attachment for her as also her life-long fidelity to him.

Here is the theory of the authorship of Gunapataka on the strength of the arguments that follows : Several writers have associated the name of Muladeva with the Art of Love.

Harihara, in his commentary on Malatimadhava actually refers to a question addressed by a certain Gunapataka to Muladeva and his answer to the query.

A similar tradition has been recorded by Yashodhara who mention Dattaka ( See my book : Vaisihhasutra : Courtesans in the Ancient India ( 2016) was approached by Courtesan through their deputy, Virasena, to guide and coach them in the Art of love and so Dattaka composed the work on Courtesans, especially for the guidance of the Courtesans of Kusumpur ( Patliputra or present Patna in Bihar).

As regards the form of the works we have reason to believe, on the strength of the quotation given by Harihara, that it chiefly in the form of a dialogue between the teacher and pupil, and that occasionally this was interspersed with a few prose passages and verses. The work ‘Uddisha Tantra, which was thoroughly studies by Koka, is in exactly this form, and several later works are also found to emulate this dialogue from.

It must be started that the work Gunapataka had no link with the work Guna Mala mentioned by Abhinavagupta ( A.D 900-1020) in his commentary on Natyashastra, since the former is certainly not a lyrical play.

Actually, Gunapataka appears to be a composition dealing generally with the Science of Erotics and, in particular, with the ways and means of attracting other women and sloping with them. As mentioned earlier, we have strong evidence in support of this presumption, and Kokkaka, the master of the science of Erotics, relies a great deal on this work for the writing of his Rati Rahasya.

To prove the importance of Gunapataka to Kukkoka for the composition of his Rati Rahasya we may refer to Parichchheda of the Rati Rahasya which echo of the earlier work ( Tantrik : 1965).

____________________

All rights reserved by the author.

Bibliography :

- Sinha, S.N and Basu, N.K : History of Prosrtitution India ( Ancient Volume -1 ) Calcutta ( 1933).

- Ray, T.N : Rati Rahasya ( Secret of Love) , ( Translated from the Sanskrit by Richard Schmidt. Calcutta ( 1950).

- Allen Edwardes : The Jewel of the Lotus ( A Historical Survey of the Sexual Culture in East ). London, SW3. (1959).

- Tantrik, Nagarjuna: Hindu Secret of Love ( 1965).

- Sinha, Indra : The Love Teaching of Kamasutra. Spring Books, London ( 1980).